Episode 50 What Logic Is, How We Know It, and Why It's Important

Apr 10, 2021 ·

1h 39m 31s

Download and listen anywhere

Download your favorite episodes and enjoy them, wherever you are! Sign up or log in now to access offline listening.

Description

In this episode, we discuss what logic really is so we can stick to the real, and so we can dismiss the misconceptions and misunderstandings of logic that are common...

show more

In this episode, we discuss what logic really is so we can stick to the real, and so we can dismiss the misconceptions and misunderstandings of logic that are common today and avoid the disasters that come with them.

We need to know what logic really is so we can better structure and sequence curriculum, as well as education overall, and we need to know what it really is so we can teach more effectively and efficiently, and so we can make it matter. We need to bring in clarity of explanation and love of life.

And every human who thinks conceptually needs to know what logic is so they can improve their thinking to improve their life: physically, socially, cognitively, emotionally, and in every way.

Show notes.

1. Basic steps to get a concept of logic (these are not all: they do not make a comprehensive and exhaustive list, but are essentials; plus, we need to get our own concrete, real examples of all this to make it real and make it knowledge; following an empty formula is neither knowledge nor understanding; we need to do the work to grasp this in each our own minds and by each our own efforts)

Experience stuff

Learn first words

Learn language and sentences

Learn that people can be wrong, can err, can make believe, can lie.

From this, we learn that we need to ID something real in the world for truth

Learn some ideas we learn later than others; some things depend on others

Learn method from algebra, geometry, or such

Generalize that method to thinking in general

Learn that we have to go through steps to be correct in all reasoning

Learn that applies to concepts, definitions, classification, induction, etc.

Logic: our means for making sure our concepts and thoughts are logically related to and derived from experience, the evidence of the senses

2. In “Aristotle” (http://galileoandeinstein.phys.virginia.edu/lectures/aristot2.html) Dr. Michael Fowler wrote:

“To summarize: Aristotle’s philosophy laid out an approach to the investigation of all natural phenomena, to determine form by detailed, systematic work, and thus arrive at final causes. His logical method of argument gave a framework for putting knowledge together, and deducing new results. He created what amounted to a fully-fledged professional scientific enterprise, on a scale comparable to a modern university science department. It must be admitted that some of his work - unfortunately, some of the physics - was not up to his usual high standards. He evidently found falling stones a lot less interesting than living creatures. Yet the sheer scale of his enterprise, unmatched in antiquity and for centuries to come, gave an authority to all his writings.

“It is perhaps worth reiterating the difference between Plato and Aristotle, who agreed with each other that the world is the product of rational design, that the philosopher investigates the form and the universal, and that the only true knowledge is that which is irrefutable. The essential difference between them was that Plato felt mathematical reasoning could arrive at the truth with little outside help, but Aristotle believed detailed empirical investigations of nature were essential if progress was to be made in understanding the natural world.”

3. In the book Galileo Galilei – When the World Stood Still, Atle Naess wrote:

“Galileo’s radical renewal sprang, nevertheless, from the Aristotelian mind set, as it was taught at the Jesuits’ Collegio Romano: human reason has a basic ability to recognize and understand the objects registered by the senses. The objects are real. They have properties that can be perceived, and then ‘further processed’ according to logical rules. These logical concepts are also real (if not in exactly the same way as the physical objects).”

4. Galileo wrote: "I should even think that in making the celestial material alterable, I contradict the doctrine of Aristotle much less than do those people who still want to keep the sky inalterable; for I am sure that he never took its inalterability to be as certain as the fact that all human reasoning must be placed second to direct experience."

From the Second Letter of Galileo Galilei to Mark Welser on Sunspots, p. 118 of Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, translated by Stillman Drake, (c) 1957 by Stillman Drake, published by Doubleday Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, New York

5. Newton’s Rules of Reasoning in Science

“Rule 1 We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.

“Rule 2 Therefore to the same natural effects we must, as far as possible, assign the same causes.

“Rule 3. The qualities of bodies, which admit neither intensification nor remission of degrees, and which are found to belong to all bodies within the reach of our experiments, are to be esteemed the universal qualities of all bodies whatsoever.

“Rule 4. In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions inferred by general induction from phenomena as accurately or very nearly true, not withstanding any contrary hypothesis that may be imagined, till such time as other phenomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions.”

6. Alan Gotthelf wrote: ”Charles Darwin's famous 1882 letter, in which he remarks that his ‘two gods’, Linnaeus and Cuvier, were ‘mere school‐boys to old Aristotle’, has been thought to be only an extravagantly worded gesture of politeness. However, a close examination of this and other Darwin letters, and of references to Aristotle in Darwin's earlier work, shows that the famous letter was written several weeks after a first, polite letter of thanks, and was carefully formulated and literally meant. Indeed, it reflected an authentic, and substantial, increase in Darwin's already high respect for Aristotle, as certain documents show. It may also have reflected some real insight on Darwin's part into the teleological aspect of Aristotle's thought, more insight than Ogle himself had achieved, as a portion of their correspondence reveals." (from: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199287956.001.0001/acprof-9780199287956-chapter-15)

7. Martyn Shuttleworth wrote: "Aristotle's zoology earns him the title of the father of biology, because of his systematic approach to classification and his use of physiology to uncover relationships between animals. He influenced Theophrastes and, whilst other Greeks and later Roman philosophers contributed, these three can lay claim to being at the starting point of the history of biology.”

And: "Aristotle's' zoology and the classification of species was his greatest contribution to the history of biology, the first known attempt to classify animals into groups according to their behavior and, most importantly, by the similarities and differences between their physiologies. Using observation and dissection, he categorized species. Although his broad classifications seem strange to modern zoologists, considering the limited equipment and store of knowledge he had access to, Aristotle's zoology stands as a tribute to his systematic methods and empirical approach to acquiring knowledge." (from: hhttps://explorable.com/aristotles-zoology)

8. Michael Boylan wrote: "What is most important in Aristotle’s accomplishments is his combination of keen observations with a critical scientific method that employs his systematic categories to solve problems in biology and then link these to other issues in human life.” (From "Aristotle: Biology" on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://www.iep.utm.edu/aris-bio/)

9. In "The Lagoon: How Aristotle invented science by Armand Marie Leroi – review" (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/oct/02/the-lagoon-armand-marie-leroi-aristotle-review) Henry Gee wrote:

Excerpt 1. "The Greeks are famous, perhaps notorious, for casting their science whole, from first principles, without troubling to examine the natural world it sought to explain. But Aristotle changed everything, providing lengthy accounts of fish and fowl, their lives, courtships, kinds, anatomies, functions, distribution and habits. They were often erroneous, but what sets Aristotle apart is his workmanlike attitude. One gets the impression of a practical man, given to neither the remote and crystalline idealism of his predecessors, nor the flights of fancy of later natural historians such as Pliny the Elder."

Excerpt 2. "Darwin knew almost nothing of Aristotle until 1882, when William Ogle, physician and classicist, sent him a copy of The Parts of Animals he'd just translated. In his note of thanks, Darwin wrote: 'From quotations which I had seen I had a high notion of Aristotle's merits, but I had not the most remote notion of what a wonderful man he was. Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways, but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle.' “

10. James Lennox wrote: "Aristotle is properly recognized as the originator of the scientific study of life. ...Aristotle was able to accomplish what he did in biology because he had given a great deal of thought to the nature of scientific inquiry. ... The goal of inquiry, he argued, was a system of concepts and propositions organized hierarchically, ultimately resting on knowledge of the essential natures of the objects of study and certain other necessary first principles."

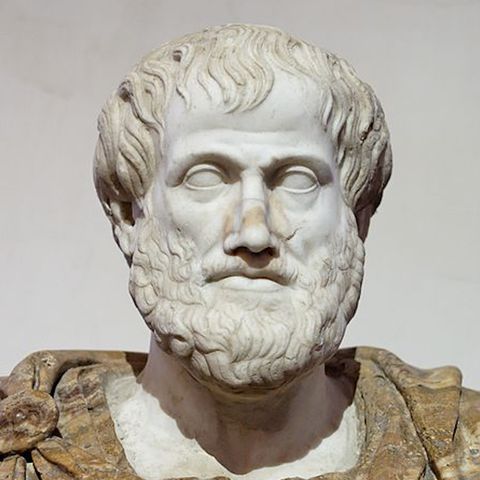

Image from Wikipedia.

show less

We need to know what logic really is so we can better structure and sequence curriculum, as well as education overall, and we need to know what it really is so we can teach more effectively and efficiently, and so we can make it matter. We need to bring in clarity of explanation and love of life.

And every human who thinks conceptually needs to know what logic is so they can improve their thinking to improve their life: physically, socially, cognitively, emotionally, and in every way.

Show notes.

1. Basic steps to get a concept of logic (these are not all: they do not make a comprehensive and exhaustive list, but are essentials; plus, we need to get our own concrete, real examples of all this to make it real and make it knowledge; following an empty formula is neither knowledge nor understanding; we need to do the work to grasp this in each our own minds and by each our own efforts)

Experience stuff

Learn first words

Learn language and sentences

Learn that people can be wrong, can err, can make believe, can lie.

From this, we learn that we need to ID something real in the world for truth

Learn some ideas we learn later than others; some things depend on others

Learn method from algebra, geometry, or such

Generalize that method to thinking in general

Learn that we have to go through steps to be correct in all reasoning

Learn that applies to concepts, definitions, classification, induction, etc.

Logic: our means for making sure our concepts and thoughts are logically related to and derived from experience, the evidence of the senses

2. In “Aristotle” (http://galileoandeinstein.phys.virginia.edu/lectures/aristot2.html) Dr. Michael Fowler wrote:

“To summarize: Aristotle’s philosophy laid out an approach to the investigation of all natural phenomena, to determine form by detailed, systematic work, and thus arrive at final causes. His logical method of argument gave a framework for putting knowledge together, and deducing new results. He created what amounted to a fully-fledged professional scientific enterprise, on a scale comparable to a modern university science department. It must be admitted that some of his work - unfortunately, some of the physics - was not up to his usual high standards. He evidently found falling stones a lot less interesting than living creatures. Yet the sheer scale of his enterprise, unmatched in antiquity and for centuries to come, gave an authority to all his writings.

“It is perhaps worth reiterating the difference between Plato and Aristotle, who agreed with each other that the world is the product of rational design, that the philosopher investigates the form and the universal, and that the only true knowledge is that which is irrefutable. The essential difference between them was that Plato felt mathematical reasoning could arrive at the truth with little outside help, but Aristotle believed detailed empirical investigations of nature were essential if progress was to be made in understanding the natural world.”

3. In the book Galileo Galilei – When the World Stood Still, Atle Naess wrote:

“Galileo’s radical renewal sprang, nevertheless, from the Aristotelian mind set, as it was taught at the Jesuits’ Collegio Romano: human reason has a basic ability to recognize and understand the objects registered by the senses. The objects are real. They have properties that can be perceived, and then ‘further processed’ according to logical rules. These logical concepts are also real (if not in exactly the same way as the physical objects).”

4. Galileo wrote: "I should even think that in making the celestial material alterable, I contradict the doctrine of Aristotle much less than do those people who still want to keep the sky inalterable; for I am sure that he never took its inalterability to be as certain as the fact that all human reasoning must be placed second to direct experience."

From the Second Letter of Galileo Galilei to Mark Welser on Sunspots, p. 118 of Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, translated by Stillman Drake, (c) 1957 by Stillman Drake, published by Doubleday Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, New York

5. Newton’s Rules of Reasoning in Science

“Rule 1 We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.

“Rule 2 Therefore to the same natural effects we must, as far as possible, assign the same causes.

“Rule 3. The qualities of bodies, which admit neither intensification nor remission of degrees, and which are found to belong to all bodies within the reach of our experiments, are to be esteemed the universal qualities of all bodies whatsoever.

“Rule 4. In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions inferred by general induction from phenomena as accurately or very nearly true, not withstanding any contrary hypothesis that may be imagined, till such time as other phenomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions.”

6. Alan Gotthelf wrote: ”Charles Darwin's famous 1882 letter, in which he remarks that his ‘two gods’, Linnaeus and Cuvier, were ‘mere school‐boys to old Aristotle’, has been thought to be only an extravagantly worded gesture of politeness. However, a close examination of this and other Darwin letters, and of references to Aristotle in Darwin's earlier work, shows that the famous letter was written several weeks after a first, polite letter of thanks, and was carefully formulated and literally meant. Indeed, it reflected an authentic, and substantial, increase in Darwin's already high respect for Aristotle, as certain documents show. It may also have reflected some real insight on Darwin's part into the teleological aspect of Aristotle's thought, more insight than Ogle himself had achieved, as a portion of their correspondence reveals." (from: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199287956.001.0001/acprof-9780199287956-chapter-15)

7. Martyn Shuttleworth wrote: "Aristotle's zoology earns him the title of the father of biology, because of his systematic approach to classification and his use of physiology to uncover relationships between animals. He influenced Theophrastes and, whilst other Greeks and later Roman philosophers contributed, these three can lay claim to being at the starting point of the history of biology.”

And: "Aristotle's' zoology and the classification of species was his greatest contribution to the history of biology, the first known attempt to classify animals into groups according to their behavior and, most importantly, by the similarities and differences between their physiologies. Using observation and dissection, he categorized species. Although his broad classifications seem strange to modern zoologists, considering the limited equipment and store of knowledge he had access to, Aristotle's zoology stands as a tribute to his systematic methods and empirical approach to acquiring knowledge." (from: hhttps://explorable.com/aristotles-zoology)

8. Michael Boylan wrote: "What is most important in Aristotle’s accomplishments is his combination of keen observations with a critical scientific method that employs his systematic categories to solve problems in biology and then link these to other issues in human life.” (From "Aristotle: Biology" on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://www.iep.utm.edu/aris-bio/)

9. In "The Lagoon: How Aristotle invented science by Armand Marie Leroi – review" (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/oct/02/the-lagoon-armand-marie-leroi-aristotle-review) Henry Gee wrote:

Excerpt 1. "The Greeks are famous, perhaps notorious, for casting their science whole, from first principles, without troubling to examine the natural world it sought to explain. But Aristotle changed everything, providing lengthy accounts of fish and fowl, their lives, courtships, kinds, anatomies, functions, distribution and habits. They were often erroneous, but what sets Aristotle apart is his workmanlike attitude. One gets the impression of a practical man, given to neither the remote and crystalline idealism of his predecessors, nor the flights of fancy of later natural historians such as Pliny the Elder."

Excerpt 2. "Darwin knew almost nothing of Aristotle until 1882, when William Ogle, physician and classicist, sent him a copy of The Parts of Animals he'd just translated. In his note of thanks, Darwin wrote: 'From quotations which I had seen I had a high notion of Aristotle's merits, but I had not the most remote notion of what a wonderful man he was. Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways, but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle.' “

10. James Lennox wrote: "Aristotle is properly recognized as the originator of the scientific study of life. ...Aristotle was able to accomplish what he did in biology because he had given a great deal of thought to the nature of scientific inquiry. ... The goal of inquiry, he argued, was a system of concepts and propositions organized hierarchically, ultimately resting on knowledge of the essential natures of the objects of study and certain other necessary first principles."

Image from Wikipedia.

Information

| Author | Michael Gold |

| Organization | Michael Gold |

| Website | - |

| Tags |

-

|

Copyright 2024 - Spreaker Inc. an iHeartMedia Company